In the year 2000, not long after taking up my role as the Institute of Physics representative in Ireland, I was part of the Irish delegation that attended the Physics on stage conference being held at CERN, the European Laboratory for Particle Physics. The first of its kind, the aim of the conference was to re-inspire physics teachers and educationalists from across Europe and to share best practice.

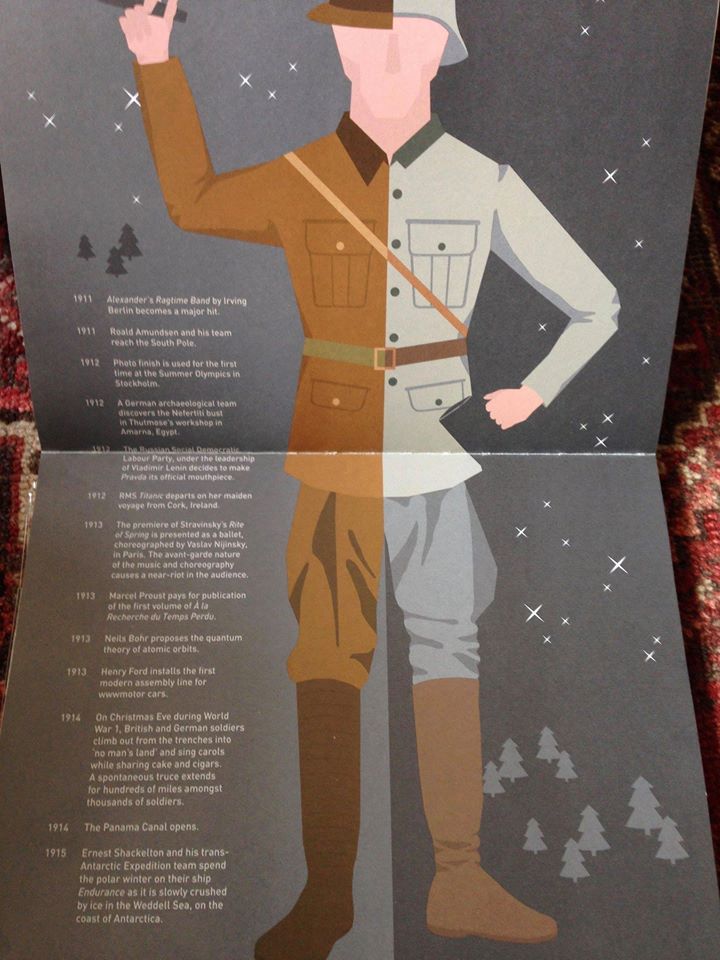

Wandering around this treasure trove of learning resources in the exhibition space, I came across a striking collage-style poster depicting a physics timeline made by school children stretching to about four metres along the wall. the extraordinary thing was that the poster did not include just physics theories and famous physicists, but, in addition, inserted above and below the physics timeline, were hundreds of other facts drawn from general history. Not only was this display teaching me physics but it was also giving the broadest and most interesting of contexts for that journey of learning.

From this germ, the concept for a Physics in Time poster was established, but not fully realised until twelve years later, by the institute of Physics in Ireland in association with the Royal Dublin Society. Significant physics discoveries since the 16th Century were presented in a timeline along with major milestones from the worlds of exploration, art, history, politics, sport and science and displayed in a striking poster. In classrooms across the length and breadth of Ireland this poster is on display – the ultimate cross-curricular resource for any school.

My desire to develop this fascinating project further culminated in the summer of 2012 when I decided to leave the institute of Physics to research, write and create a follow on to the poster – The Visual Time Traveller: a graphically curated narrative of history, art and science since the Renaissance.

With such a plethora of information available, the book needed a couple of structural rules. Firstly, a maximum of twelve facts would be included on any list. Only the surface could be

skimmed, yet it would provide a trail of stepping-stones from which readers could take off on their own historical journeys. Secondly, the design to go with each list would be developed with a fresh concept and typography, providing a platform for innovative design to drive the narrative of historic facts.

Philosophical thoughts often hovered while I was compiling the longer lists for the book. What is history? Is it the truth? The truth is a complex thing, hard to pin down. Birth dates are known, we know when papers were published and who was victorious in which battle but we don’t always know how conclusions were made or whether credit was simply being taken by those with the savviest PR skills of the day or by the documentary proof of being the first to get into print. Pertinent examples include the calculus controversy between Newton and Leibnitz and the airbrushing of Robert Hooke’s image out of history – no paintings of Hooke’s likeness have survived. The firm ground of historical fact can easily turn into a quicksand of doubt.

While researching, the urge to mine deeper was always present and often imperative. seeking earlier sources of information, spiking off on tangents and adding to an exploding and chaotic file called ‘more information’ became the norm. An initial bald fact would flower into a resonant nuanced story and I had a growing conviction that there are very few original ideas out there – so many echo back to classical times. Themes and ideas reverberate through the ages, tapping on our shoulders lest we forget how often the past becomes our present.

The opening and closing pages of this book are marked by two powerful inventions that have profoundly influenced our ability to communicate and share information – the Gutenberg Printing Press and the World Wide Web. Printing was the main way to disseminate ideas in the sixteenth century so it is apposite that Francis Bacon wrote ‘Knowledge is Power’ and printed it in his book Meditationes Sacrae in 1597. Finance and permission to print were the limiting factors for any communicator hundreds of years ago but the thirst for information was always strong: when Galileo’s Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems was banned in 1633, its price increased twelve-fold on the black market such was the demand for the book. Furthermore it was smuggled across the alps to Strasbourg to be translated into Latin for distribution in Europe – preventing the spread of knowledge is like trying to stop water from owing downhill.

Now, in the 21st century, our problem is not about getting enough information but about having too much and how to make sense of it all. The creative approach to the graphic elements of the book offered a welcome way to soothe this information overload. Weaving fact and illustration, hero and event, personal and political, the care and passion in the art direction went far beyond the initial vision. Possibilities opened up and excitement was palpable when we saw what could be created by integrating the printed word with creative design.

Whimsy and personal politics (from which few writers can hide) have played their part in these selections. I always kept one eye on the facts and events that most people would expect to see, but countered it with space for the individual and the curious. Ensuring a stronger female presence on the page was a challenge but what a joy to find amusing, fascinating or forgotten details about women. For example, when in the University of Rome, medical student Maria Montessori was required to perform her dissections of cadavers alone, after hours. Attending classes with men in the presence of a naked body was deemed inappropriate!

History is punctuated by conflict and resolution, yet war has made only a brief entrance to this narrative, to mark a century or decade rather than to dominate the theme. In this spirit, there can be no better time to honour than Christmas eve in 1914, when British and German soldiers climbed out of their trenches into No Man’s Land and sang carols while sharing cake and cigars. A spontaneous truce extended for hundreds of miles amongst thousands of soldiers. War and peace indeed.

Exploration, philosophy, art and science have marched inexorably forward since the dawn of civilization. A rich fabric stretches out behind us but we only need to look back for a moment to glimpse a few of its silken threads.

Bon voyage.

Alison Hackett

Picture caption 1910 – 1915 in The Visual Time Traveller: 500 Years of History Art and Science in 100 Unique Designs